Taking an environmentally sensitive approach to pest management

Monitoring, Detection and Management of Lettuce Drop caused by Sclerotinia spp.

Published: February 1, 2016

Biology and life cycle of the lettuce drop fungi

The fungal pathogens in the genus Sclerotinia are known to cause diseases that are difficult to deal with on a wide range of crops. Lettuce is affected by two of these species, S.sclerotiorum and S.minor. Either of the two species may predominate on a given farm at a particular time. Both species may also exist in the same field as long as the prevailing weather favors them and, more importantly, based on the crop histories. S.minor is not a common problem of lettuce here in Missouri but S.sclerotiorum affects many vegetables (including lettuce) as well as grain crops such as soybeans.

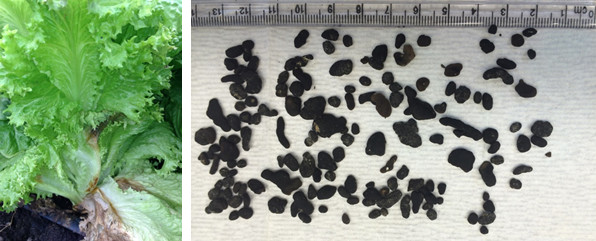

On lettuce, the type of damage inflicted by these fungi has two phases depending on when it started: a) the damping-off phase which attacks the seedling stages, and b) the field phase which causes a watery soft rot of lower leaves and crown areas (Fig. 1, left). This is followed by wilting and limping, leading to an obvious symptom commonly referred as DROP. Lettuce drop caused by Sclerotinia species is known to be a serious problem of lettuce production worldwide. Both species produce black, hard, seed-like resting bodies called sclerotia (sing. sclerotium) on the lower surface of the leaves touching the soil, around the crown, and on the upper portion of the taproots. Sclerotia may survive in the soil for up to 8-10 years. Occasionally, both pathogens may also survive as active mycelium in diseased or dead lettuce plants. Sclerotia of S.minor are small (1/16 to 1/8 inch) and irregular in shape; in contrast, sclerotia of S.sclerotiorum which are larger (up to ½ to 1 inch) and are oblong to irregular and may appear similar in shape to rodent fecal pellets (Fig.1, right).

Fig. 1. Initial symptom of lettuce drop on variety ‘Rex’ (left) and sclerotia of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (right) from heavily diseased high tunnel lettuce grown in Missouri.

What do the symptoms and signs of lettuce drop look like?

The initial symptom of lettuce drop is wilting of the outermost layer of leaves which is usually observed as the crop approaches maturity. This symptom indicates that the crown has become infected. As infection progresses, the crown will develop a brown, soft, watery decay followed by the development of a snowy-white mycelium that eventually destroys the tissue and causes the entire plant to wilt (Figs. 2 and 3). Collapsed plants are unharvestable (Figs. 3 and 4). Typical signs of drop disease include white, fluffy, cottony mycelial growth during cool and moist weather, and the black sclerotial bodies on leaf undersides and crown area (Fig. 4). With S.minor, only the white mycelium and small black sclerotia are formed. S. sclerotiorum may also produce a mushroom-like structure called an apothecium which emerges from the sclerotia and produces ascospores. These ascospores disperse in the air and may cause infections on the tops of lettuce plants.

Fig. 2. Challenged by what is killing your lettuce? Check for the initial symptoms on the bottom leaves/crown area and keep a suspect plant in a plastic bag with a paper towel overnight to see the fluffy mycelial growth.

Fig. 3. Typical fluffy mycelium of the lettuce drop and sclerotia of S. sclerotiorum seen when the fluffy mass of an infected red oak leaf lettuce plant is removed.

Fig. 4. Contrast of healthy and lettuce drop symptomatic red and green oak leaf lettuce grown in high tunnel.

Fig. 5. Signs of the fluffy mycelium of Sclerotinia crown and stem rot on high tunnel kale grown in central Missouri.

Under what conditions does the pathogen thrive?

Sclerotia, the hard bodies produced by both Sclerotinia species, allows these lettuce drop pathogens to survive in the soil. Soil moisture that is maintained at saturation for two or more weeks will lead to germination of the sclerotia of S.sclerotiorum, the fungus responsible for causing lettuce drop in Missouri. Temperatures between 59 to 71°F are optimal for the growth of S.sclerotiorum; therefore, cool, damp conditions favor pathogen growth and disease development. Lettuce is a cool season crop in Missouri. Accordingly, plantings particularly in protected systems (e.g., tunnels and greenhouses) from fall to early spring are highly susceptible to this disease.

How is lettuce drop managed?

- Scout for and discard infected plants. Infected plants need to be detected as early as possible and be discarded before they form sclerotia. Bear in mind that once formed, sclerotia are capable of staying in your soil for up to 8-10 years.

- Remove and destroy crop residue. As much as possible, all litter and infected plant parts from previous crops should be removed and destroyed. Avoid discarding infected material at the field edge as it can blow back into the field.

- Avoid planting after other known hosts. Rotation with non-hosts such as small grains should be practiced where it is feasible. Some possible rotation crops include onion, spinach, small grains or grasses. Other known crop hosts of Sclerotinia diseases include beans, cauliflower, celery, endive, escarole, fennel, pepper, radicchio, and tomato. On tomatoes, S. sclerotiorum causes a disease called timber rot. Cover crops to avoid include Australian winter pea, mustard, phacelia, and vetch.

- Moisture management. Manage irrigations so as to avoid overly wet soils which may encourage Sclerotinia development. The use of sub-surface drip irrigation may reduce lettuce drop severity. Level production fields and provide even distribution of water. In addition, assure good drainage by having beds as high as possible. Flooding the soil when the ground is not in production could also help to reduce survival of sclerotia, particularly that of S. minor.

- Avoid crowding of plants. Crowding of lettuce plants in the field, high tunnels, or greenhouses may create a fertile ground for epidemics of the lettuce drop disease. Opening up space randomly throughout the beds during harvesting will improve ventilation and significantly reduce the plant-to-plant contact and hence spread of the disease. In addition, lettuce planted on narrower beds may have lower incidences of drop than lettuce planted on wide beds.

- Nutrient management. Avoid overly succulent growth by keeping the fertilizer level as optimum as possible.

- Deep (inversion) plowing. Inverting and burying the top layers of the soil by using mold board plows may provide adequate control in fields with low sclerotial densities. Some research has shown that deeply buried sclerotia will die over time, or not be able to reach the lettuce plant. This results in reduced inoculum presence.

- Soil fumigation. Soil fumigants are effective in reducing inoculum. However, such treatments are usually not cost-effective, due to a) the high price of fumigants and b) the labor required applying the chemicals. In addition, the accompanying safety regulations due to their toxicity make their feasibility on small scale very difficult.

- Resistant varieties. Breeding efforts are underway and but truly resistant varieties are not yet available. Varieties with upright growth in which the leaves are more or less elevated from the soil may experience less severe lettuce drop.

- Biological control. Contans WG® at 1-4 lbs. per acre, an OMRI (Organic Material Review Institute) approved product, is recommended for many Sclerotinia diseases including lettuce drop. It is also widely used for controlling white mold on beans. Contans®, whose active ingredient is the beneficial fungus Coniothyrium minitans, is applied with conventional spray equipment directly to the soil surface at planting. For more information on the product label follow this link http://www.cdms.net/ldat/ld5SH001.pdf. Since the active ingredient of Contans WG® is a biological organism, its efficacy depends on how the product is stored and applied. It has a short shelf life and hence keeping it under cool temperature is critical. Get the area well prepared ahead of time. Effectiveness is dependent on proper timing of the application, optimum soil moisture (too dry soil may hamper efficacy), and thoroughness of the coverage.

Fig. 6. Pilot projects on the use of biofungicide Contans® WG in high-tunnels in Missouri. Left: Ms. Martha O’Connor, Extension Technician at Lincoln University Cooperative Extension, is spraying Contans® WG in a high tunnel (around the time of sunset). Middle: lettuce in a hightunnel with an estimated 25% lettuce drop incidence in April 2014. Right: the same high tunnel after two applications of Contans® WG (2 lb/A) planted with lettuce in November 2014.

- Conventional fungicides*. A significant reduction in lettuce drop was reported by applying fungicides during the rosette stage (approximately 30-40 days before harvest). Split applications of fungicides resulted in even better control. Generally, however, fungicides applied after thinning do not generally reduce lettuce drop caused by S. sclerotiorum. The following are recommended (Source: 2016 Midwest Vegetable Production Guide) products (conventional growers) against lettuce drop: Botran 75W® or Botran 5F® (rate varies by application method), Endura 70WG® (8-11 oz. per acre), Fontelis® (16-24 fl. oz. per acre), Merivon® (8-11 fl. oz. per acre) and Switch 62.5WG® (11-14 oz. per acre). Pay attention to the Pre-Harvest Interval (PHI) of each product. * These are options for non-organic farms. For S. minor, fungicides applied immediately after thinning and cultivation (at 4-6 true-leaf stages) have shown a significant reduction in incidence of lettuce drop.

- Integrated lettuce drop management. An integrated approach involves the use of the multiple strategies listed above to manage the disease and thereby increase productivity and profitability. Sclerotinia diseases are difficult to deal with. Depending on the season, location and level of inoculum, implementing as many compatible methods as possible is highly recommended. For detailed information on integrated approaches, refer to the publication by Subbarao (1998).

Before applying ANY product, 1) read the label to be sure that the product is labeled for the crop and the disease you intend to control, 2) read and understand the safety precautions and application restrictions, and 3) make sure that the brand name product is listed in your Organic System Plan and approved by your certifier (organic growers).

Trade names in this publication are used solely for the purpose of providing specific information. Such use herein is not a guarantee or warranty of the products named and does not signify that they are approved to the exclusion of others. Mention of a proprietary product does not constitute an endorsement nor does it imply lack of efficacy of similar products not mentioned. Do not use any of the products unless registered for the given crop in the state.

References:

-

CDMS Contans® WG label. Available at: http://www.cdms.net/ldat/ld5SH001.pdf.

-

Egel S. D., Foster R., Maynard E., Weinzierl R., Babadoost M., O’Malley P., Nair A., Cloyd R., Rivard C., Kennelly M., Hutchison B., Piñero J., Welty C., Doohan D., Miller S. (eds.). Midwest Vegetable Production Guide for Commercial Growers.

-

Subbarao, K. V. 1997. Lettuce Drop. Pages 19-21 in: Compendium of Lettuce Diseases. R. M. Davis, K. V. Subbarao, R. N. Raid, and E. A. Kurtz, eds. American Phytopathological Society, St. Paul, MN.

-

Subbarao K. V. 1998. Progress Toward Integrated Management of Lettuce Drop. Plant Disease 82: 1068-1078.

Subscribe to receive similar articles sent directly to your inbox!

REVISED: February 2, 2016